Alcântara Caneiro

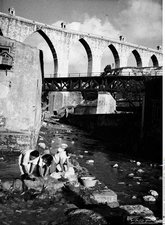

How many have heard of it, but know little about it? Many even associate it with sewage, some not so much. Others, who are older, talk and know about the stream - the Alcântara Stream - which used to run from Amadora to the Tagus, where boats used to sail, where clothes were washed and children played, where there was industry, agriculture on fertile land, lime kilns and even a tide mill.

The growth of cities is inevitably linked to the search for solutions for the disposal of human waste, which was usually dumped in gutters and streams. The Caneiro de Alcântara was a consequence of the growth of the city of Lisbon.

We went to find out about it. Its "birth", what it went through and what it is today. We did our research and visited it, guided by someone who knows it like no one else: Fernando Fernandes, a technician from the Lisbon City Council's Sanitation department, who told us about its origins, why it was built and how important it still is today.

Through the bowels of the city

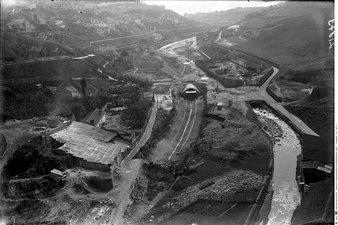

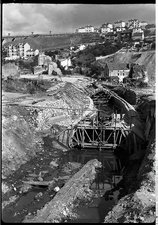

Next to Quinta do Zé Pinto, in Campolide, where preparations are underway to open a tunnel that will connect Monsanto to Chelas as part of Lisbon's General Drainage Plan and reduce the risk of flooding in the Alcântara area, we come to the old canyon.

This is where the branches that bring wastewater from downstream flow: the Benfica branch and the Sete Rios branch .

Still outside, to the sound of the metallic clang of the machine preparing the entrance to the tunneling machine responsible for opening the new tunnel, a kind of giant hammer, we put on our protective suits.

The smell already makes us turn up our noses. "It's only for two or three minutes, then you get used to it," says one of the technicians who helps us, by way of reassurance, and then warns us that "gloves should never be taken off". Inside, it's a breeding ground for microbes and bacteria, and a significant part of the city's sewage passes through it. A mask is also necessary: "If anyone has problems breathing in stuffy places, let us know so we can be vigilant."

As we descend the wide, deep access shaft, the adrenaline rises. It's a strange sensation to enter the bowels of the city, a dark, cold tunnel that is nevertheless strangely beautiful. Because of its size, because of its symbolism, because of the brown water that flows freely, like a river, because of the darkness on the horizon, dappled with small lights that guide the expedition.

We only walked five hundred meters. More or less. Enough to understand its size, to feel it.

Back and forth, workers pass us with handcarts. Empty there, full here. Full of debris which, later on, we'll see flowing from a small side gallery. It's the result of drilling on the surface, and it has to be removed.

There are several side galleries, which Fernando Fernandes explains were the first accesses to the canyon. It was only later, and as it became necessary, that larger entrances were built, such as the one through which we began our exploration.

Zealous technicians accompany us. They're like canyon doctors, looking for illnesses and finding cures. They belong to the collector inspection team, which is supporting our visit at the moment, particularly in creating safety conditions. Some of them have recently been recruited and are still in training, our cicerone explains to us.

We turn back, always amazed by the huge concrete tunnel. We climb back up to the surface, panting. Our bodies are sweating from the action of the white robes, a kind of monkey suit reminiscent of those worn by the scientific police, which we hastily get rid of. And the gloves. And the masks. The smell, which seemed to have disappeared downstairs, will keep us company for some time to come, even for the next few days.

Up here, the city continues its hustle and bustle, down there the river of its waste continues its journey. It goes on and on, but now it's no longer heading towards the river, as it was when the canyon was built, because further on it's diverted towards the Wastewater Treatment Plant.

A transverse wall, about 1.30 m high, takes care of this.

An old and unhealthy problem

"As early as the mid-18th century, the Alcântara Stream had been identified as a source of unhealthiness in the city of Lisbon, specifically in the Alcântara district," Fernando Fernandes tells us.

It was a problem that worsened over time, as unhealthy water from many of Lisbon's houses, and some from Falagueira (now part of the municipality of Amadora), flowed through the river.

In Municipal Magazine no. 27, 1945, we find an interesting approach to the city's public hygiene problems ("Grandes Problemas de Lisboa - Caneiro de Alcântara", Revista Municipal de Lisboa, 4th quarter 1945.

It states that, since the 15th century, "there were pipes in the capital", which "served little purpose other than to drain the meteoric waters". Domestic waste was deposited on the beaches, in the mountains or directly in the streets.

The first known official order to clean the drains dates back to 1484, the article adds, and two years later a royal charter ordered the construction of "first and second order drains" in the city's main streets, as well as preventing drains from leaking into the streets before the "hour of the bell".

In 1871, Lisbon had 82 main pipes that served as sewers for houses and streets, and it is reported that "one of them was the one that had its boqueirão to the Alcântara caneiro."

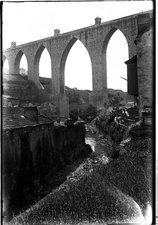

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/PAG/000021 Alcântara Stream by the New Bridge [c. 1912]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/2/2/csm_17_b2ec018258.jpg)

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/PAG/000022 Washing women in the Alcântara Stream by the New Bridge [c. 1912]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/2/c/csm_18_464a61ce3a.jpg)

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/PAG/000023 Washing women in the Alcântara Stream by the New Bridge [c. 1912]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/8/0/csm_19_1065a94afb.jpg)

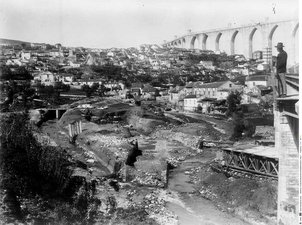

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/PAG/000555 Alcântara stream near the Tarujo bridge [c. 1912]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/7/a/csm_20_761bfaf881.jpg)

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/PAG/000560 The Alcântara stream in the Rabicha area [c. 1912]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/9/e/csm_22_fa68ec38cc.jpg)

The problems of insalubrity were such that we consider it important to transcribe the following excerpt from the document in full:

"With its ten-kilometer length along the western edge of the Monsanto mountain range, from the heights of Falagueira to the Tagus, the Alcântara stream has, since ancient times, been an exceptionally acute problem in the capital's sanitation concerns. Considered the most important drainage basin in Lisbon's sanitation system, as it covers an area of 4,689 hectares including 321,000 inhabitants (58 percent of the system's total area), its watershed receives, in addition to rainwater, the urban sewage corresponding to a large part of Lisbon's urbanized area - perhaps half a city. It serves as a dumping ground for waste of all kinds, especially from the small, poor settlements along its course - Rabicha, Sete Moinhos, Cascalheira, Liberdade, Santana, Quintinha, Vila Pouca and Ponte Nova.

This stream, which, as you can see, acts as a general collector for the sewage networks of large urbanized areas - Avenidas Novas, Palhavã, Benfica, Carnide, the entire Alcântara valley with Campolide, Campo de Ourique, Estrela, etc., runs under the open sky (...)."

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/MAO/000021 Rabicha Bridge over the Alcântara Stream [c. 1940]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/6/8/csm_34_efb68d05ff.jpg)

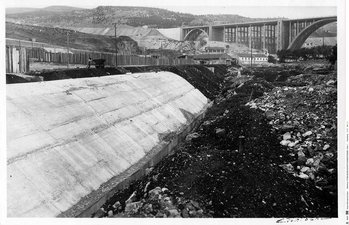

When construction began in 1945, public health and the sanitary conditions of the surrounding neighbourhoods were the main reasons for piping the river, but the urbanization plan for the Alcântara valley was also a powerful incentive.

There was only one section already piped, downstream. At the end of the 19th century, part of the stream had been covered for the laying of the railroad that connected Alcântara-Terra to Campolide, and from there to Sintra and Torres Vedras, and then the works for the 1st section of the Port of Lisbon covered the part that flows into the River Tagus.

It was during this period that the old Alcântara bridge disappeared, a Roman stone construction built over the Ribeira de Alcântara, next to Rua Prior do Crato (formerly Rua Direita do Livramento). This bridge, it should be noted, gave the parish its name - from the Arabic al-quantãrã: "the bridge".

A major undertaking

We went back to talk to Fernando Fernandes to find out that the project to canalize the stream was drawn up in the 1930s and completed in 1939.

The work was only started in 1945 and completed at the end of 1967; it was inaugurated on January 5, 1968, at Portas de Benfica, he tells us [It was put out to tender on March 14, 1944 and the contract was awarded on May 1 of that year, for 21,723,277$60. Preliminary work began in December 1944, but it wasn't until June 1945 that concreting began, due to a shortage of cement, a problem that was eventually overcome].

"It's a huge project and it was done in phases," he says: "The first phase, what we call the downstream section, which runs between where we are, Campolide, and the Alcântara area. Specifically, the Alcântara-Terra station. This phase took place between 1945 and 1950; from 1955 to 1968 the second phase was built, what we call the Benfica and Sete Rios branches."

It was built in simple concrete and Fernando Fernandes points out that it is a section "designed specifically for this work, which even had the collaboration of some American universities." The maximum dimension is eight meters wide by 5.15 meters high and it stretches for about ten kilometers.

Even today, it is of great importance in draining a substantial part of the city's domestic wastewater and rainwater, even more so given the urban and population growth, with the consequent sealing of the soil.

![EN/AMLSB/CMLSBAH/PCSP/004/PAG/000018 Alcântara Stream by the New Bridge [c. 1912]](/fileadmin/informacao/_processed_/3/9/csm_16_01175b8c55.jpg)

Keeper of the Canary

Fernando Fernandes: Sanitation Technician; he has worked at Lisbon City Council for 44 years, in Sanitation for 34.

"Working in the sanitation sector, and particularly in the city of Lisbon, is a constant challenge that promotes continuous professional and personal evolution and development. It is very motivating to know that we are working to continuously improve the quality of life in our city and to promote environmental protection and, in this way, make our contribution to the community."